Links: https://what3words.com/headless.perch.snares

Only a few Anglo-Saxon battles have managed to escape the realm of specialist interest and capture the imagination of the general public. The Battle of Maldon, that took place in 991CE between local forces and Viking invaders, is one of these.

The main reason for this level of interest is probably the Old English poem that is usually called ‘The Battle of Maldon’. If it had a different title this is lost as the the beginning and end of the poem are missing, but there are still 325 lines which provide lots of interesting detail. However these were also nearly lost as in 1731 the only known manuscript of the poem was destroyed in the fire. Thankfully a copy had been made only a few years before, which is the version we have today.

During the latter part of the 10th century the English royal policy on how to respond to Viking raids was divided. Some advocated for paying off the Viking invaders, while others believed that combat was the more effective strategy. The poem indicates that a Byrhtnoth, who was a Ealdorman of Essex favoured combat.

The poem describes how the Vikings sailed up the River Blackwater and the Anglo-Saxons under Byrhtnoth’s command came to face them. His forces included a number of trained troops, complemented by local farmers and villagers who formed a militia called the Essex ‘fyrd’. The Vikings landed on a small island connected to the mainland by a land bridge during low tide. They offered to depart if paid, but Byrhtnoth refused.

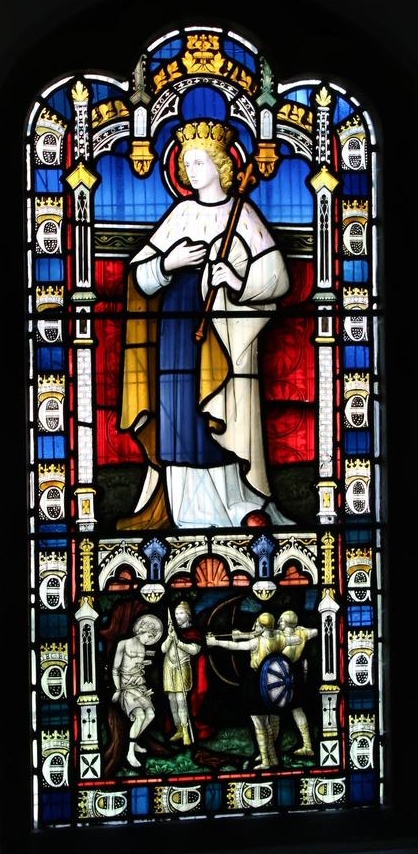

As the tide receded, the Vikings initiated an assault across the land bridge. However, three select Anglo-Saxon warriors, Wulfstan, Ælfhere, and Maccus, successfully thwarted their advance. The Viking commander, who is nameless in the poem, then requested that Byrhtnoth allow his forces onto the shore for a formal battle, and for an unknown reason, Byrhtnoth consented. The battle commenced, but at a pivotal moment, an Englishman named Godrīc seized Byrhtnoth’s horse and fled. His brothers followed him and subsequently many Anglo-Saxons who mistook the person on the horse for Byrhtnoth also fled, thinking he was abandoning them. This caused confusion, allowing the Vikings to defeat the Saxons, albeit with significant losses. Tragically, Byrhtnoth was killed, and his decapitated body was later found with his gold-hilted sword still by his side.

Although we know the general location, battlefields of this period are infamously difficult to pin down. So the poem, with it’s detail is a great help in finding the exact location. Following the many clues in the poem, Northey Island which is 2km to the east of Maldon seems to be the best match. Today it is still linked to the mainland by a land-bridge which is submerged at high tide, but is likely much longer today than it would have been at the time. Unfortunately there is very little archaeological evidence to confirm it is the site. Byrhtnoth’s body was taken to the Ely cathedral to be buried and it is likely that lots of other bodies were removed.

Byrhtnoth’s death and the sacrifice of his retainers who fought on after his beheading seem to have saved Maldon from immediate attack. However whatever losses the Viking’s sustained, both in men and a lack of payment, it did nothing to stop them returning to Essex later. It may also have caused the king at that time, Ethelred the Unready, to give in and pay the Vikings what is called Danegeld, something he gathered through imposing taxes on his subjects.

Byrhtnoth’s sacrifice has lived on. It inspired J.R.R. Tolkien to write a poem published just before ‘The Fellowship of the Rings’, in which two men retrieve his body from the battlefield. Then in 2006 a statue of him, created by a locally born sculptor, was installed at the end of the Maldon breakwater, forever looking down the River Blackwater and continuing his guardianship of Maldon.

Links:

- Dave Beard ‘The Battle of Maldon’, Medieval World 1991 – http://archeurope.com/@pdf/battle_of_maldon.pdf

- historic England Report – https://historicengland.org.uk/content/docs/listing/battlefields/maldon/ Wikipedia page – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Maldon

- Text of the poem – https://oldenglishpoetry.camden.rutgers.edu/battle-of-maldon/